What defines the perfect speed skating blade? Hans Gijsen is introducing us to the wonderful world of rockers and stiff blades

They seem to be rock solid under your boots: your blades. But there is a lot going on under your feet. That rocker is not as static as you think and the metal is more flexible than you would imagine. Hans Gijsen explains how you can make this your advantage.

'I always skate a rocker of 23, I don't want anything else', you often hear skaters say on the rink. It seems logical, never change a running system. You are feeling good on your blades, so why try something new? “That sounds like rubbish to me”, says skating mechanic Hans Gijsen. He sees it differently. “You might want it to be that easy, but it’s definitely not the case.” he says firmly. The blade may be sharpened into that radius, but when you start skating on it, the situation changes entirely. “It's a dynamic situation.” he explains. “I will try to explain.” He wrote the book "The rocker and the bend." (The Competition Skate) in which he explains in detail, but is not afraid to explain it all again.

Strong and flexible

It surprises me how flexible the blade is that Hans shows me. You can easily bend it like a simple metal ruler. “Look, this is what we all skate on. That's pretty flexible, isn't it?" he is grinning. The point is made pretty fast: the blade is made of partially hardened bi-metal, but that doesn't determine the stiffness. “The tube that holds the blade determines the stability and flexibility of the blade. Especially if there is a lot of pulling and pushing going on. That tube determines how well the blade holds its shape,” he explains smiling. “A very strong and still very flexible skate, that's what you want,” he continues, pointing to extremely stiff tubes, like the Cadomotus “Pressure”. “Once that skate is in place and keeps its shape, it doesn't have to do anything anymore.” That can make a big difference in the event of a misstep or a crash. A skate with a tube of a lesser quality will remain permanently bent after a misstep or a crash, while the skate of a better steel type simply pops back into its original shape.

The rocker is not absolute

The steel seems almost alive, bending under pressure and giving in to our weight and that has a huge effect on the rocker, too. It seems to be a constant value, but that’s not the case. “Some things are not as non-relative as they seem,” Gijsen explains. “I'm working on making sure that a skate is sharpened in a perfect 23m radius, but that’s not what the skaters are actually skating on. They are skating on a variable event and that’s what I am trying to explain in my book. This applies to all types of skates. Last week I made a graph concerning a blade which had been sharpened in a very accurate rocker of 23. After sharpening the blades, I check the rocker. The gauge (instrument to measure the rocker) has a pointer that doesn't move at all, if the rocker is perfect. Each inconsistency of the rocker makes the pointer shake but if you are actually going to skate on it and your body weight is pushing the middle of the blade into the ice, your rocker changes completely. You might be skating on a 33m radius now. If you weigh 40kg, you might be skating on a 26m radius, while a heavy skater who weighs about 100 km might neutralize the radius almost completely. He skates on a 37m radius.”

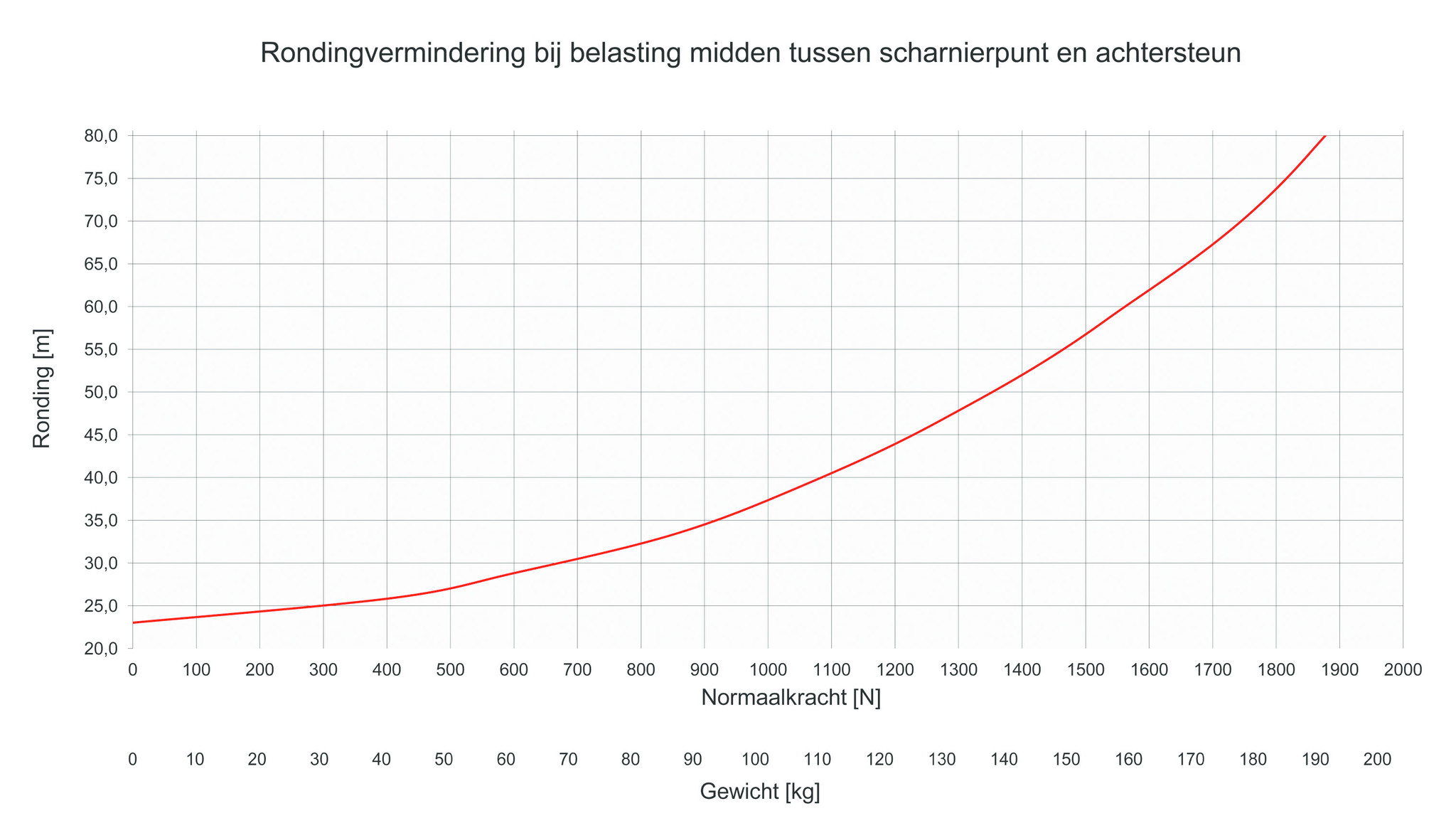

Fig.1 Changing of the rocker during skating

It is not static, Gijsen explains. While skating you are constantly in motion, which makes the rocker work differently in every phase of the movement. See the graph above. “The center of gravity moves gradually towards the pivot point during the push, before the skate opens. The maximal force is reached just before that. Since your position on the ice is very obliquely at this point, the rocker changes back to its original radius: when your weight is pushing on the pivot point, you only push on one spot of the blade. So the blade does not move. Thus your rocker changes from 46 or so, to 45, 44, 38 and then, to 23. Just during one push” Hans pauses for a moment and continues somewhat surprised: “Everyone is used to it, you can't change it and that is actually very typical. There is a big difference between light and heavy skaters. And also between large and small skates. Heavy skaters often have large skates, the support points are far apart and they sink deeper into the ice. With larger skates you would actually have to put the support points closer together in order to create a better skating experience.”

Gauge deviation

Meanwhile, many skaters are obsessed with that perfect rocker, says Hans. A machine made radius is almost never perfect, he explains. When you move the gauge over the blade the pointer often moves all over the place, which is proof enough that the radius is not perfect at all. “That’s what I show the skaters,” he says. “Most of them have their own gauge, too." The skaters talk to each other and the stability of the pointer becomes a kind of quality mark. They tell each other: The pointer must stay in the same place. But always be aware, he warns. “They might say: it indicates 35 micrometres and it is a rocker 23. Every gauge, if you buy it from the factory, even the best ones have a deviation of about 2 micrometres. That's exactly one meter of radius difference. So if the gauge indicates 35 micrometres, your blade has a 23m radius, if it shows 36.3, it's already a 22m radius, and at 38, is at 21m. A gauge can't really tell you the exact radius. If it reads 30, it could also be 28. You can only use it to check the evenness of a rocker.” As far as he is concerned, you can only determine the exact rocker on the measuring table.

Variable rocker

As far as he is concerned, there is still some room for improvement in the way we shape our blades. “You would have to experiment with a variable rocker, like it's done in short track. Skaters feel that immediately, if you do that and it is not easy to skate on, because skaters often do not believe that it will work. I have done experiments with a variable rocker with some skaters. With good results and they still skated personal best times. But if they skate on the blades a whole season, in the end it is difficult to tell whether the rocker made the difference. It could also be the physical shape. Could I have skated faster on my old blades? You just don't know. It all comes down to what the skater feels.”

Feelings can be deceiving

The adjustment of a skate remains a matter of feeling. Your frame of reference is what you're used to. But by measuring you can equalize the basic conditions. For example, if you're trying out a new skate, you should actually be skating with the exact same rocker and the same height of the blade. Many skaters experience a new skate as quite different, while there is often hardly any difference. “They don't believe it, even if you tell them” concludes Hans Gijsen. “They are feeling something but they can't exactly tell what it is. So you compare their blades. And it turns out: this skate is completely different than the one they are already skating on. Their own blade has another rocker and has been sharpened. So the rocker has changed over time and the blade is not the same height anymore. That's what they feel.”

[NEWSLETTER]